By Chris Marshall

The only flies I used when I first began to fiddle with a fly rod were sparsely-tied, soft-hackled patterns.

I grew up in a moorland valley in the southwest corner of Yorkshire. As far back as I can remember, I was fascinated by the river which ran through the valley and the fish which lived in it and its tributaries. I taught myself to catch trout with a fly by carefully observing the few local anglers who practiced the art. The flies were all wet patterns and almost all wingless but they were very effective in the turbulent freestone streams we fished.

Today, I still use them in my home waters in Ontario, as well as in the freestone rivers of the North Eastern USA. For even though the basic design of the patterns is hundreds of years old, it is deadly for fishing for trout and other species in fast water anywhere in the world.

Part One – Origins

There are a number of references in the literature to simple hackled flies going back to the Middle Ages, but it isn’t until the nineteenth century that we find any kind of systematic treatment in English, and it’s not surprising that all of these were written by fly fishers in places where the rivers ran fast and rough—south-western and northern England. The most prominent were three Yorkshiremen: John Jackson (The Practical Fly Fisher, 1853), John Kirkbride (The Northern Angler, 1855), Michael Theakston (British Angling Flies, 1883

All were careful observers of the natural insect and the flies they tied and used were designed to imitate these. However, the imitation had little to do with configuration and proportion and everything to do with size, colour and action. The tiny body (some were bodiless) and sparse, soft hackle enabled the fly to sink and undulate enticingly as it tumbled downstream in the manner of a dislodged nymph, struggling emerger, swamped dun, or drowned spinner.

However, early in the twentieth century H.H. Edmonds and N.N. Lee considered that the nomenclature, prescription of materials, and proliferation of patterns found in the work of these writers of the previous century, tended to confuse “modern” fly fishers. Consequently, they published Brook and River Trouting (1916), which was an attempt to synthesise and simplify what had gone before.

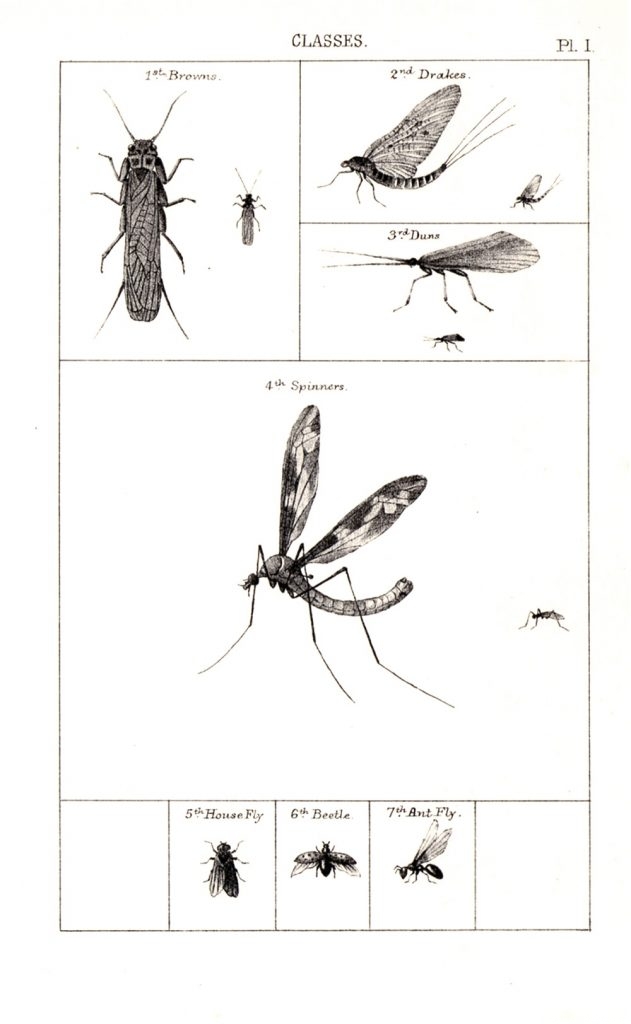

In a number of respects, Edmunds and Lee were justified in their complaints. For instance, Theakston invented his own peculiar nomenclature for classifying natural insects: Drakes” for mayflies, “Browns” for stoneflies, “Duns” for caddis flies, and “Spinners” for crane flies and midges. To say that this system could be confusing to modern anglers is a major understatement. Similarly, there is considerable inconsistency among the nineteenth century writers with respect to the names, sources and colours of feathers. Perhaps the most pervasive of these, is their use of the word “bloa”, for some it’s used to refer to a kind of feather, for others to refer to a species of natural fly or its imitation, while yet others simply use it to describe a specific colour (the dark purplish-blue found in thunderclouds or bruises), and some add to the confusion by using it for all three.

Despite this, there’s much of value for modern soft-hackled fly fishers in the work of the nineteenth century writers.

Soft Hackle Tips from the Nineteenth Century:

The Necessity for Precise Observation and Imitation

While less rigorous than the demands of match-the-hatch, the principal nineteenth century chroniclers were adamant that fly fishers scrutinise the natural insects carefully and and tie their flies to imitate their colours and their movement in the water. For instance, Theakston based his patterns on precise observation of the naturals on his home rivers in the Yorkshire Dales, mainly the River Ure, and advocated that “the natural flies, the theme of this book, are the first and only principals; they are nature’s living pattern, food of the fish, which is the gem of the fly fisher’s art to copy”.

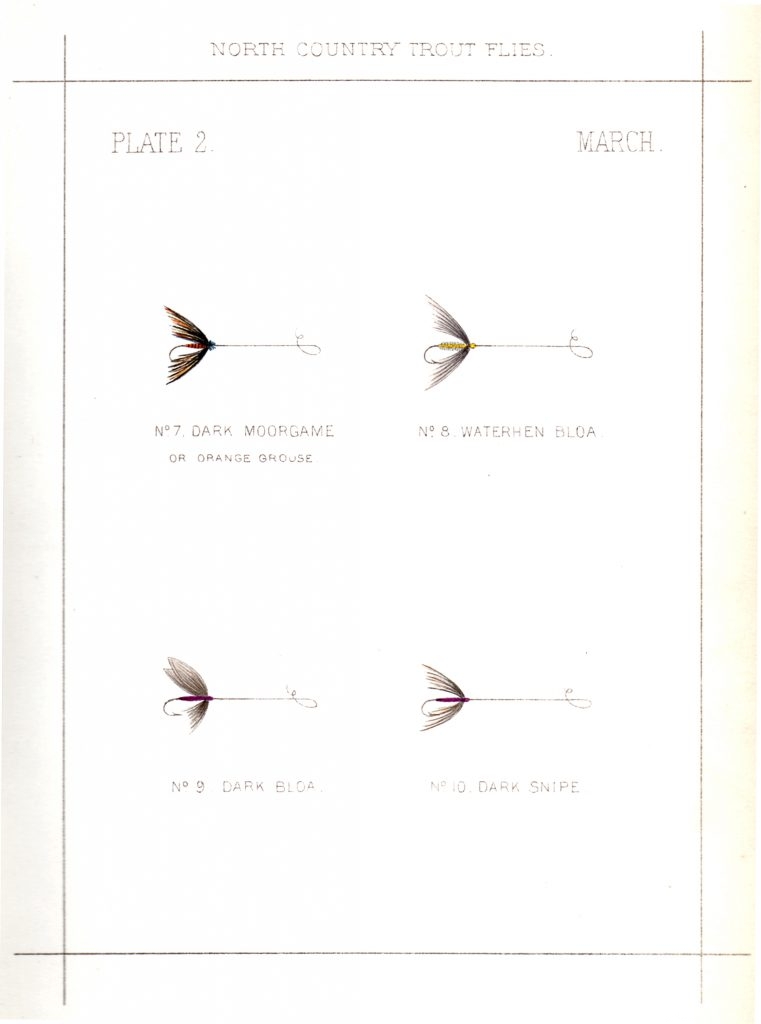

All the major writers also suggested varying patterns to imitate the seasonal progression of hatches of fly species. Kirkbride for instance, observes that “our anglers are content with three or four sorts [of fly], for they vary the shades as the season advances.” In fact, the convention in all the major writers is to organise their lists of fly patterns on a seasonal basis.

Sparseness

There was a universal insistence that flies be tied sparsely—that the bodies should be short and slim (often just wraps of silk) and that hackles should be confined to just a couple of winds.

Materials

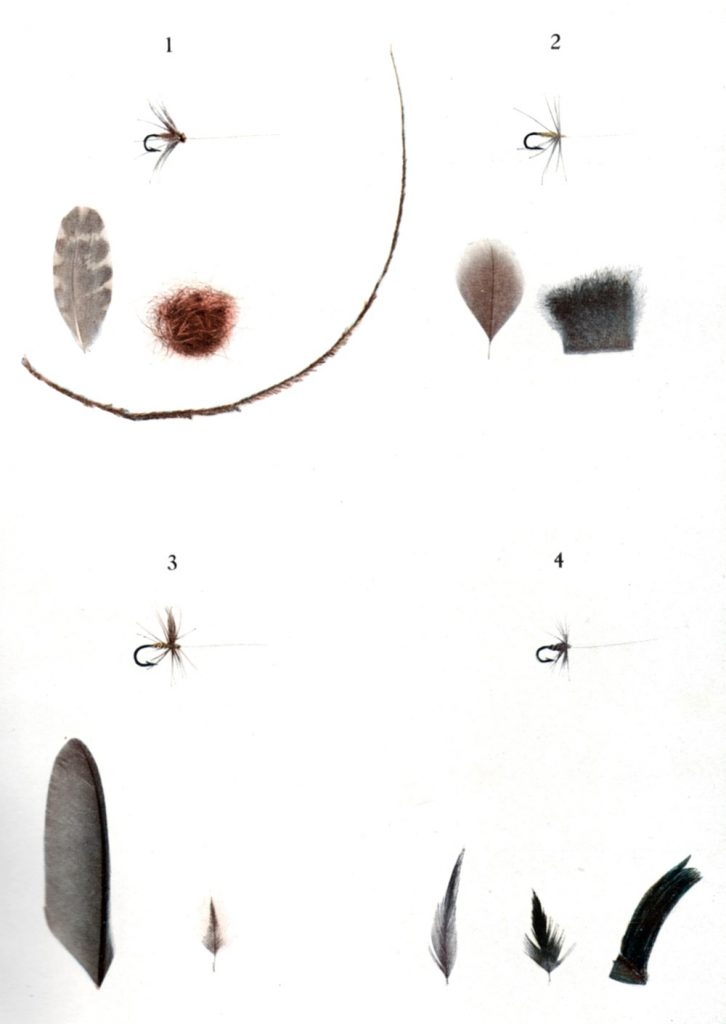

While there are undoubtably conflicting and often confusing instructions among the nineteenth century writer about the nature and source of materials, generally they all provide useful suggestions. With respect to some materials, there’s clear consensus—on using pure silk thread for tying and building bodies, for instance.

Moreover, Edmonds and Lee, benefitting from over 20 years of technological development, were able to provide colour plates of excellent, detailed illustrations of materials, their sources and the finished flies, and is still the best source for modern tyers wishing to tie north-country patterns.